The Evolution of Time Series Forecasting - From Statistical Methods to Foundation Models

When forecasting met foundation models

Hi, I’m Mark — welcome to Tech Accelerator!

A newsletter dedicated to exploring the fast-moving world of AI - from foundation models and agentic systems to robotics and enterprise transformation.

I break down the key innovations, trends and market shifts shaping how AI is built, deployed and scaled across industries.

💡 Join thousands of readers who receive Tech Accelerator directly in their inbox — free and designed for leaders building the AI future.

🔗 For daily AI insights and real-time updates: https://www.linkedin.com/in/markkovarski/

🔗 More technical focus AI (Incl. research papers, model releases, robotics updates and more): https://x.com/mkovarski

This edition is all about a business workhorse that quietly powers everything, time series forecasting, and how it’s evolved into the foundation model era today.

For decades, forecasting remained largely unchanged. Businesses relied on ARIMA models developed in the 1970s, statisticians manually tuned parameters for each individual time series and on top the accuracy plateaued around only 50-60%. Each new forecasting problem, whether predicting retail demand, traffic patterns, or energy consumption required building and training a model.

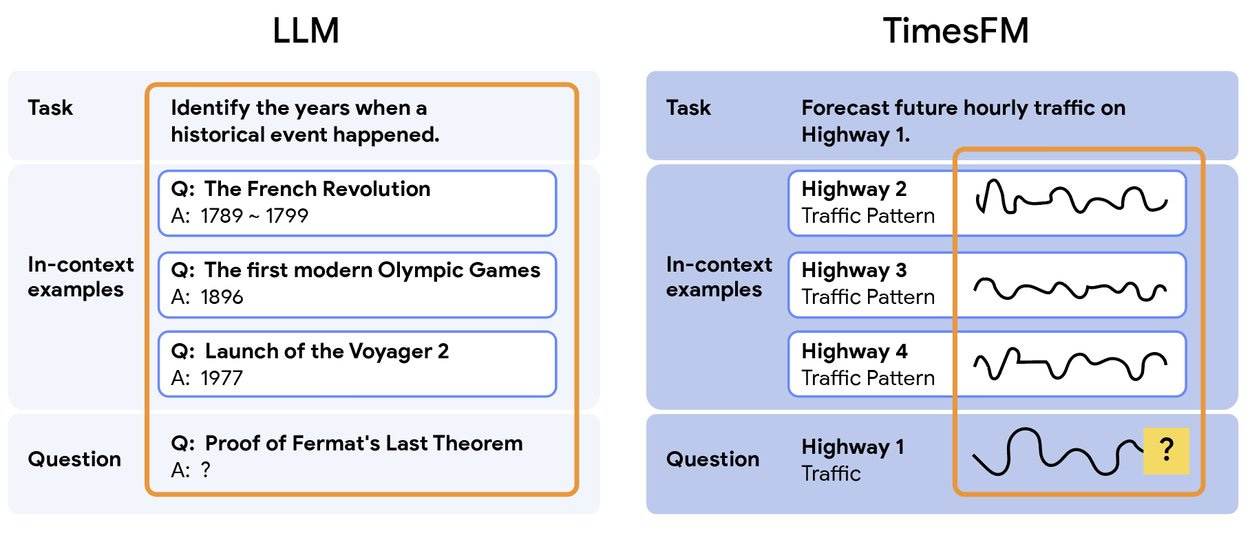

In natural language processing, models like GPT transformed AI by demonstrating a powerful capability: pre-train once on diverse data, then apply it to countless new tasks. Ask ChatGPT about the French Revolution or the launch of Voyager 2, and it can answer.

Over the past 18 months, this same approach has transformed time series forecasting. Foundation models like Google’s TimesFM, Amazon’s Chronos, and Salesforce’s MOIRAI are pre-trained on billions of observations from various domains, retail sales, web traffic, energy demand, sensor readings, then applied to new, unseen time series. This “zero-shot” forecasting capability represents a fundamental shift in how the field operates now.

The transformation in numbers:

Amazon’s Chronos family: 600+ million downloads from Hugging Face.

71% of data scientists now exploring zero-shot or foundation model techniques.

58% of enterprises have upgraded to transformer-based forecasting models.

Walmart reduced food waste by $86 million in six months using ML forecasting systems.

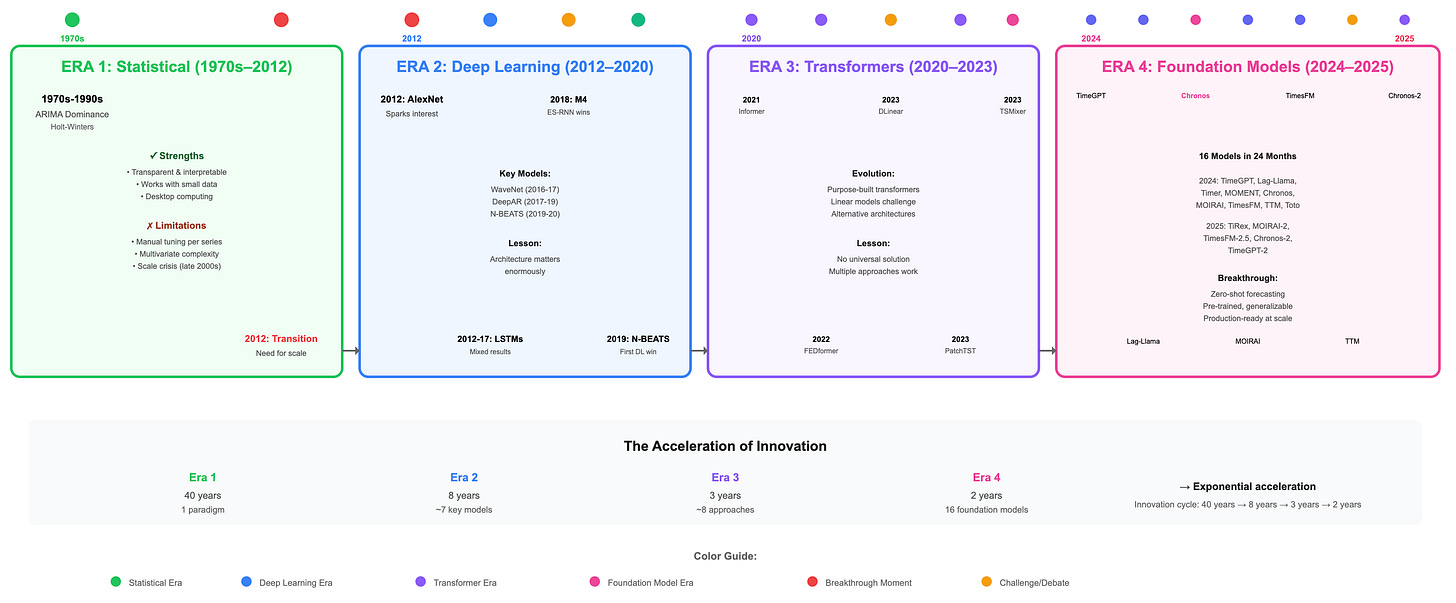

But this didn’t happen overnight. From statistical methods in the 1970s through deep learning’s emergence in 2012, to transformers in 2020 and finally to foundation models in 2024, each era built on lessons from the last.

This is how we got here and where forecasting is heading next.

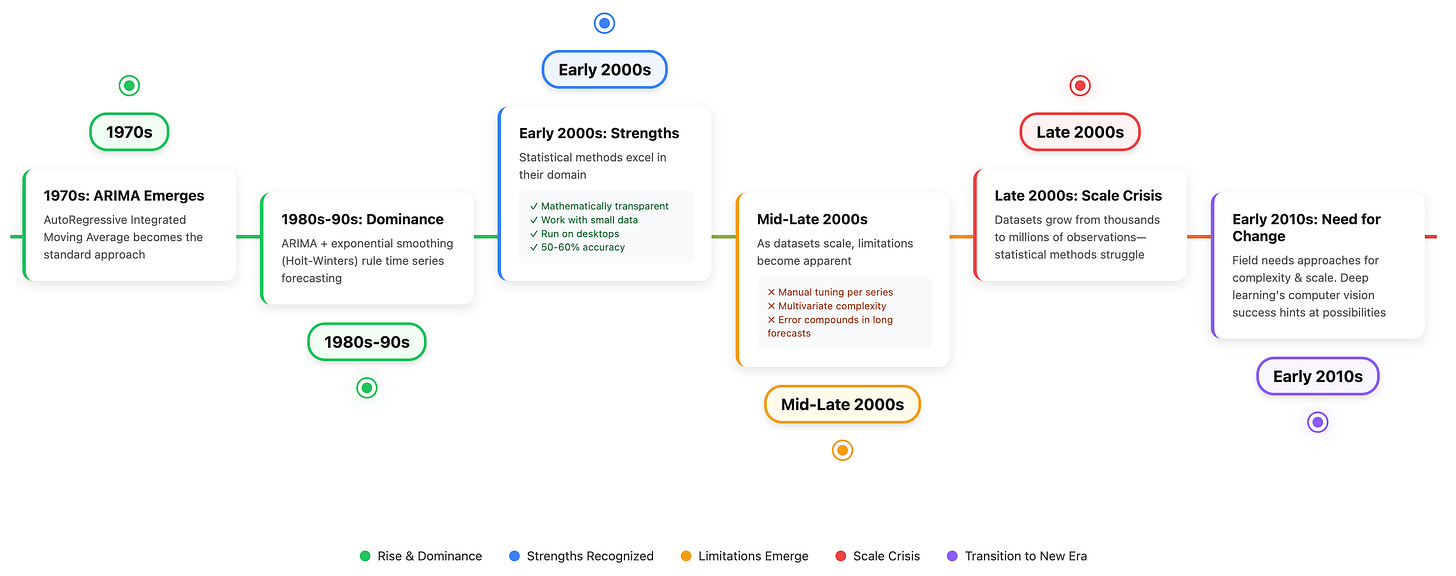

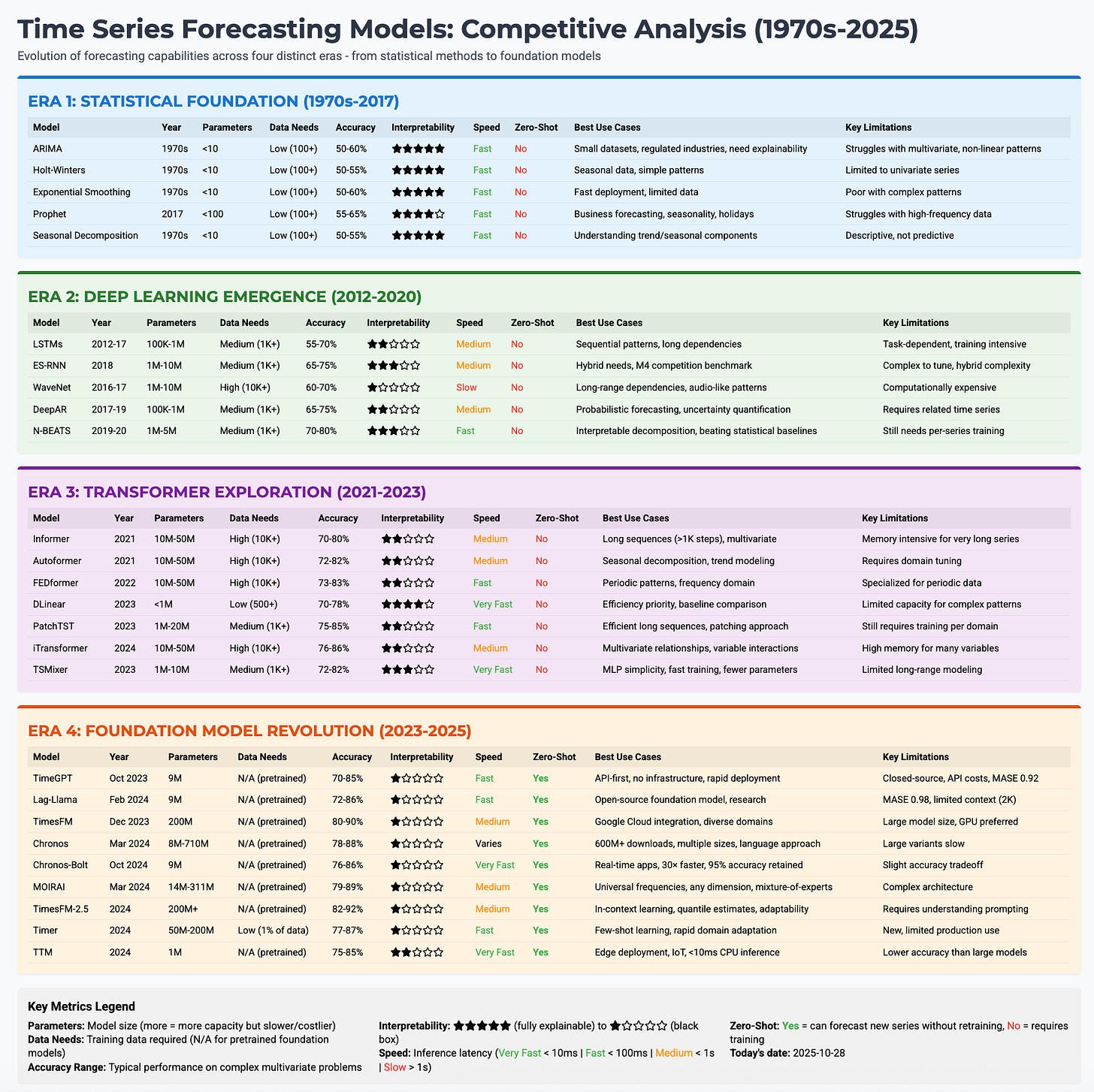

Era 1: The Statistical Foundation (1970s–2012)

Before neural networks entered the field, time series forecasting was primarily a statistical discipline. ARIMA (AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average) was used from the 1970s through the 2000s, alongside exponential smoothing methods like Holt-Winters. These approaches proved effective for their era, offering mathematically transparent models that practitioners could understand and explain. They delivered good forecasting performance with just a few hundred observations and ran efficiently on desktop computers.

However, as datasets grew from thousands to millions of observations and problems became increasingly multivariate, the limitations became apparent. Each new time series required its own stationarity checks, differencing operations and parameter tuning, all of this didn’t scale well. Traditional statistical methods struggled to capture patterns, and their long-term forecasts were riddled with more errors. While these tools performed well on individual series, they proved inadequate for simultaneously processing thousands of related time series.

By the early 2010s, the field needed approaches capable of handling greater complexity and scale. Deep learning’s success in computer vision and natural language processing at that time suggested that neural networks could offer new capabilities, setting the stage for changes in forecasting methodology.

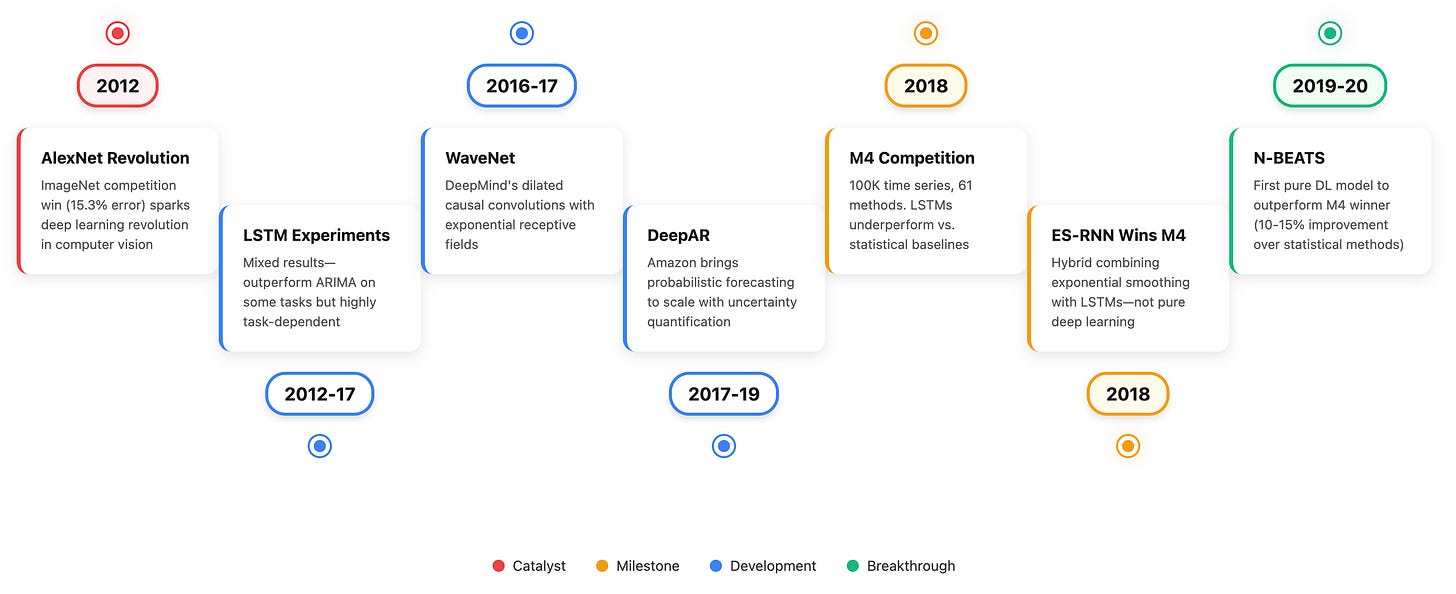

Era 2: Deep Learning’s Emergence (2012–2020)

When AlexNet won the 2012 ImageNet competition with a 15.3% top-5 error rate, beating the runner-up by 10.8 percentage points, it demonstrated deep learning’s potential. Researchers naturally wondered whether similar approaches could improve time series forecasting.

Between 2012 and 2017, researchers experimented with LSTMs (Long Short-Term Memory networks), which possessed the memory capabilities theoretically suited for forecasting. Results were mixed. While LSTMs outperformed ARIMA on many tasks, particularly for capturing non-linear patterns and long-term dependencies, their success proved highly task-dependent.

The 2018 M4 Forecasting Competition provided an important benchmark. Across 100,000 time series and 61 forecasting methods, LSTMs underperformed relative to simpler statistical baselines. This outcome raised questions about why deep learning, so effective in vision and language, showed more limited gains with numerical time sequences. Notably, the M4 winner wasn’t pure deep learning, it was actually ES-RNN, a hybrid combining exponential smoothing with LSTMs. This suggested that integrating traditional statistical methods with neural networks might be more effective than replacement.

Despite these mixed results, several well-designed architectures demonstrated progress:

WaveNet (2016-2017): DeepMind’s dilated causal convolutions with exponential receptive fields enabled parallelizable training. Originally designed for audio generation, it proved effective for time series as well.

DeepAR (2017-2019): Amazon brought probabilistic forecasting to scale, enabling uncertainty quantification through distribution estimates rather than just point predictions.

N-BEATS (2019-2020): The first deep learning model to outperform the M4 competition winner across different benchmarks, showing 10-15% accuracy improvements over the best statistical methods at that time.

By 2020, the field had established that deep learning could work for time series. This foundation prepared the ground for transformer-based approaches.

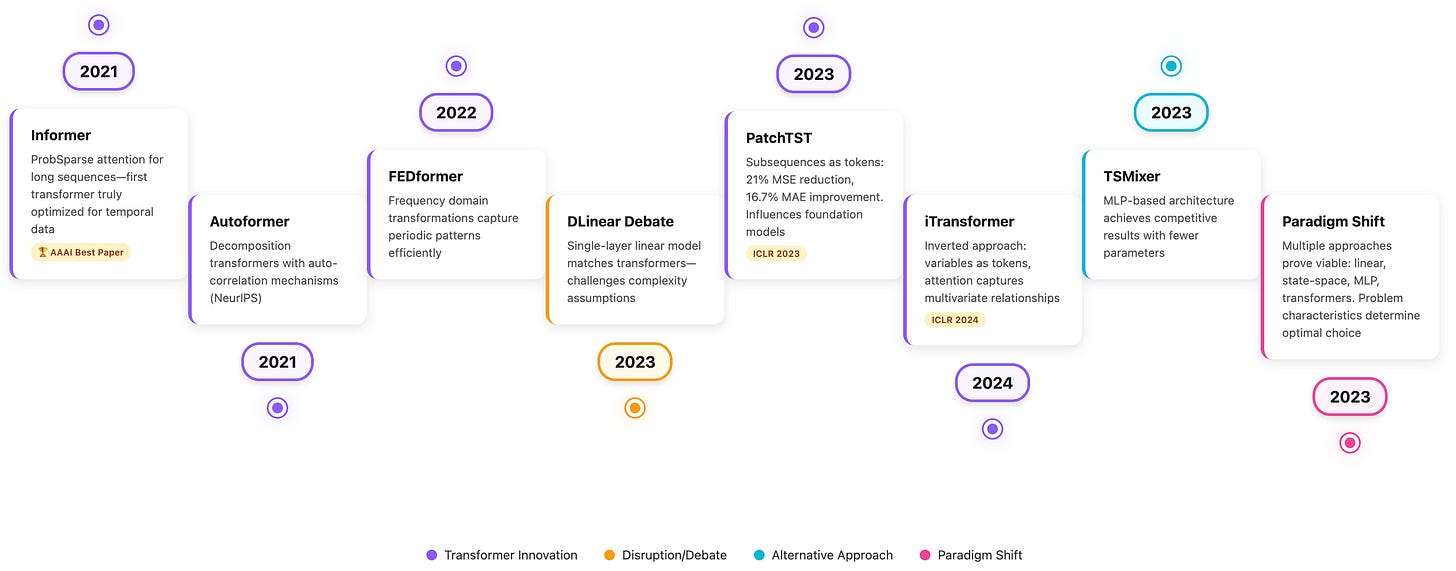

Era 3: The Transformer Exploration (2020–2023)

After transformers changed natural language processing, researchers looked at whether they could similarly advance time series forecasting. This period showed some important lessons about architectural choices and the value of domain-specific design.

Early transformer architectures adapted:

Informer (2021): Won the AAAI 2021 Best Paper Award by introducing ProbSparse attention mechanisms designed for time series. This represented the first transformer architecture truly optimized for temporal data.

Autoformer (2021): Introduced decomposition transformers with auto-correlation mechanisms at NeurIPS 2021. By explicitly modeling trend and seasonal components, it achieved notable performance gains and inspired subsequent architectures.

FEDformer (2022): Applied frequency domain transformations to capture periodic patterns more efficiently than time-domain attention.

Then came DLinear (2023), a straightforward single-layer linear model with seasonal decomposition that performed comparably to many transformer baselines across multiple benchmarks.

Several innovations demonstrated clear contributions:

PatchTST (ICLR 2023): Treated subsequences (16-64 steps) as tokens, maintaining local temporal structure while reducing sequence length by 10-20×. Achieved 21% MSE reduction and 16.7% MAE improvement over earlier transformer baselines. The patching technique later influenced foundation models like TimesFM and Chronos-Bolt.

iTransformer (ICLR 2024): Inverted the standard approach by treating variables as tokens rather than time steps, allowing attention to capture multivariate relationships while feedforward networks modeled temporal patterns.

TSMixer (2023): Demonstrated that MLP-based architectures could achieve competitive results with fewer parameters than full transformers, questioning the necessity of attention mechanisms for all forecasting tasks.

By 2023, the field recognized that multiple approaches showed good merit. Linear models, state-space models like Mamba, MLP architectures, and various transformer designs all showed competitive performance on different benchmarks. The best choice depends on various problem characteristics including data volume, dimensionality, forecast horizon needs , budgets and also interpretability requirements.

Era 4: The Foundation Model Era (2023–Present)

After Era 3 showed everyone that no single architecture will dominate so the field pivoted toward foundation models, large pre-trained models designed to generalize across various forecasting tasks through zero-shot or few-shot learning. This approach marked a shift from training separate models.

The foundation model landscape evolved:

TimeGPT (Nixtla, October 2023): First time series foundation model. 9M params trained on 100B observations (finance, retail, energy). Closed-source API-only approach. MASE 0.92 on M4 monthly; struggled on daily frequencies.

Lag-Llama (Morgan Stanley/ServiceNow, February 2024): First open-source foundation model. Llama-based, 9M params, 2,048 context length. Apache 2.0 license. MASE 0.98 on M4.

Timer (Tsinghua THUML, February 2024): GPT-style decoder, 84M params, 260B training points. Unified forecasting, imputation, and anomaly detection. Few-shot: 95% performance with 1% training data. ICML 2024.

MOMENT (Carnegie Mellon, February 2024): T5 encoder, 385M params. Multi-task: forecasting (MAE 0.45), classification (82% accuracy), anomaly detection (F1 0.73), imputation (MSE 0.32).

Chronos (Amazon, March 2024): T5 encoder-decoder. Tokenized time series as language. 100B observations + synthetic data. Sizes: 20M-710M params. Strong zero-shot performance across domains. Apache 2.0 license. 600M+ downloads.

MOIRAI (Salesforce, April 2024): Encoder-only. Multi-patch layers (8-128 timesteps), any-variate attention (1-100+ variables). 27B observations across 9 domains. Sizes: 14M, 91M, 311M params. Top-3 on 27 benchmarks.

TimesFM (Google, May 2024): Decoder-only, 200M params, 100B training points. Adaptive patching (32-in/128-out), 512 context. BigQuery integration. MASE 1.02; particularly strong on daily frequencies.

Tiny Time Mixers/TTM (IBM, June 2024): Non-transformer MLP, ≤1M params (<1% of large models). TSMixer-derived with adaptive patching. <10ms CPU inference. MASE 0.94. 99% cost reduction.

Toto (Datadog, July 2024): First domain-specialized foundation model. 151M params, 2.36 trillion tokens (70% proprietary telemetry from 500K+ environments). IT observability optimized. 15-20% better on IT metrics.

Timer-XL (Tsinghua THUML, October 2024): Extended Timer. 2,880 context (5.6× increase), up to 100 covariates. 8-12% accuracy gains on long-horizon forecasts (>100 steps).

Chronos-Bolt (Amazon, November 2024): Speed-optimized. 250× faster inference (2.5s → 10ms), 20× better memory (4GB → 200MB), 5% lower error. 100K forecasts/second on single GPU.

TiRex (NXAI, May 2025): First successful LSTM-based foundation model. xLSTM architecture, 35M params (5% of Chronos Large). #1 on GIFT-Eval: MASE 0.88. 18% better on sparse data (>25% zeros). Training cost: <$5K.

MOIRAI-2 (Salesforce, August 2025): Decoder-only with multi-token predictions. 16% better MASE, 44% faster inference (45ms → 25ms), 96% smaller (311M → 12M params). #1 on GIFT-Eval non-leaking: MASE 0.86, CRPS 0.24.

TimesFM-2.5 (Google, September 2025): 200M params (60% reduction), 16K context (8× increase). Native probabilistic forecasting. #1 zero-shot on GIFT-Eval: MASE 0.84, CRPS 0.22. 15ms inference, 500MB memory. BigQuery + Vertex AI integration.

Chronos-2 (Amazon, October 2025): Universal forecasting. Supports univariate, multivariate (200 variables), covariates (50 features). Group attention mechanisms. 21 quantiles, 8,192 context. Sizes: 20M-710M params. 90%+ win rate vs Chronos-Bolt (95%+ on covariate tasks). 25-100ms inference.

TimeGPT-2 (Nixtla, October 2025): Three versions—Mini (47M params, <15ms), Standard (200M params, 30ms), Pro (650M params, 85ms). 60% accuracy improvement over v1. Self-hosting option. 10M+ forecasts daily for Fortune 1000. Top-3 on GIFT-Eval: MASE 0.87.

Over the past ~18-24 months, foundation models evolved with significant advancements being made. Parameter counts grew from 9M to 710M (Sweet spot is 12-200M). Context windows expanded from 512 to 16K timesteps. Training data scaled from millions to 100B+ observations (Toto: 2.36 trillion tokens). Capabilities progressed from single-task to universal forecasting supporting univariate, multivariate and covariate inputs. Models now provide forecasting with quantile estimation rather than point predictions. Inference speeds improved from seconds to milliseconds.

Traditional approaches required training separate models for each time series or careful hyperparameter tuning for each domain. Foundation models work across various datasets, from retail sales to energy demand to IoT sensor readings, without task-specific training. A retailer can apply the same model to forecast demand across 100,000 SKUs, website traffic, and supply chain metrics simultaneously. When zero-shot performance proves insufficient, foundation models adapt to specific datasets with minimal examples needs. Timer demonstrated 95% of full training performance using just 1% of training data, while TimesFM-2.5’s in-context learning enables further customization.

TimesFM-2.5, Chronos-2, and MOIRAI-2 all provide quantile estimates, enabling businesses to express uncertainty: “we’re 80% confident revenue will be between $900K and $1.5M” rather than simply “we forecast $1.2M in revenue.” This improves risk management across applications. Chronos-2’s group attention mechanism enables forecasting that considers historical time series data (univariate or multivariate), external covariates (weather, holidays, promotional calendars, economic indicators), and cross-series relationships. This unified approach captures complex dependencies that traditional methods handled through manual feature engineering or separate models.

Time Series Foundation Models - Navigating the Options

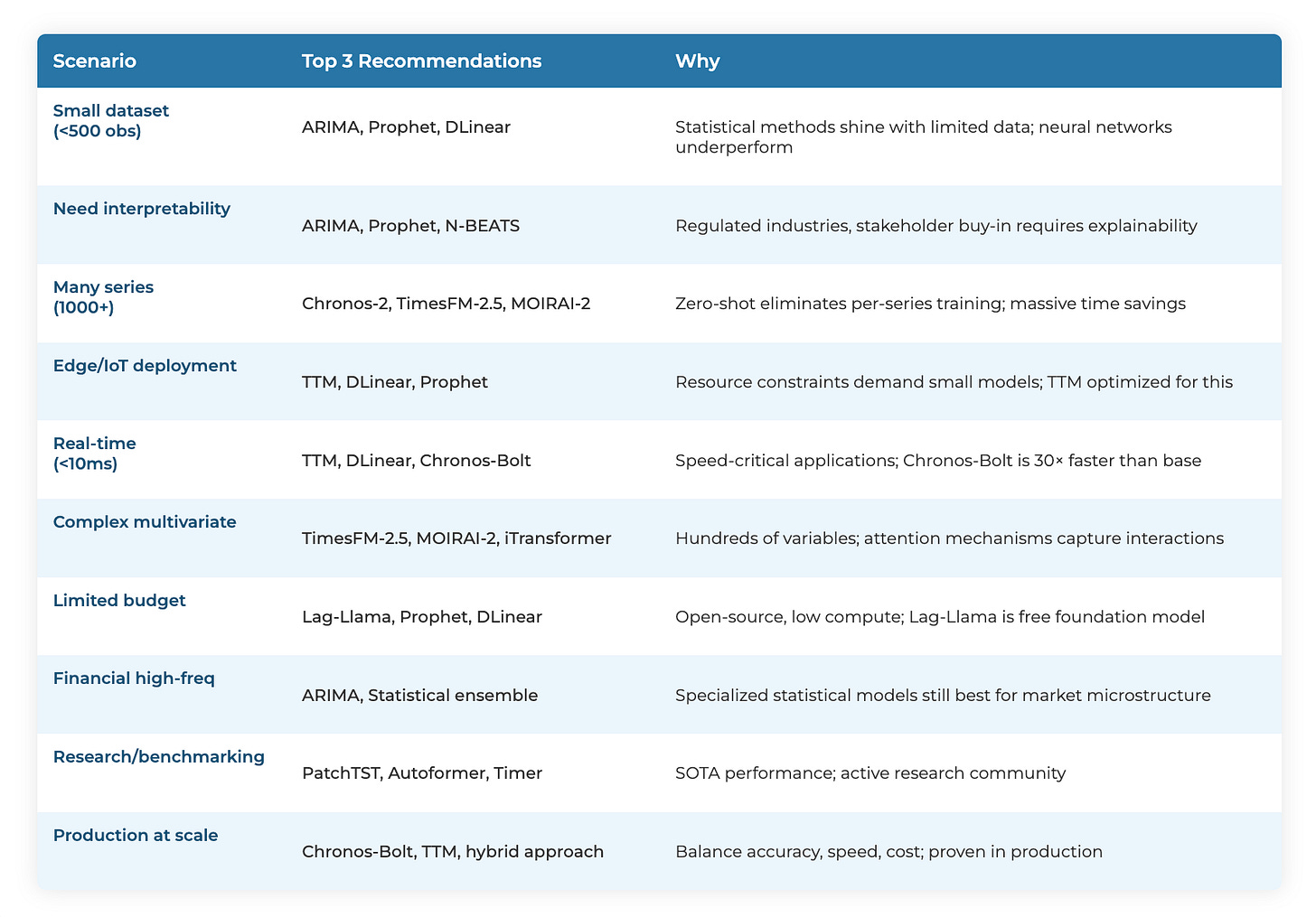

After several decades of evolution, the forecasting field now offers more tools than ever before. This creates a new challenge, knowing which tool to use when. The foundation model discussed in Era 4 might be overkill for some problems or insufficient for others. Success depends on truly understanding what’s available and when each approach is best.

Classical Statistical Methods

ARIMA, exponential smoothing, Prophet, and seasonal decomposition didn’t disappear when neural networks arrived. They remain highly effective for specific use cases: small datasets (<500 observations), regulated industries and others. When forecasting with just 100 observations, ARIMA often outperforms neural networks.

State Space Models

Mamba and similar architectures offer linear-time sequence modeling as alternatives to transformers, delivering better efficiency for long contexts. These are good for streaming data, continuous learning and various resource-constrained environments.

MLP-Based Approaches

TSMixer, TTM, and N-BEATS achieve competitive performance with simpler architectures. They train faster, require less memory and often work well with smaller datasets.

Hybrid Methods

The M4 forecasting competition demonstrated that the winner wasn’t pure deep learning or pure statistics, it was ES-RNN combined exponential smoothing with neural networks. This approach suits production systems requiring both performance and reliability, particularly for organizations transitioning from statistical to ML methods.

Purpose-Built Transformers

PatchTST, iTransformer, and Informer represent architectures designed specifically for temporal patterns rather than generic transformers adapted for time series. These work best for large-scale multivariate forecasting, research and problems where accuracy is important.

Foundation Models

TimesFM, Chronos, MOIRAI, and TimeGPT represent the newest paradigm: pre-train once on diverse data, then forecast new series without retraining. Their primary advantage is zero-shot generalization, forecasting time series the model has never seen before.

Performance has improved significantly. Statistical methods from the mid-2010s achieved 50-60% accuracy on problems, while modern foundation models reach 75-90% accuracy. Foundation models show their strongest advantages with complex multivariate patterns involving hundreds of interacting variables, large-scale forecasting tasks (thousands to millions of series).

The organizations achieving the best results maintain several forecasting portfolios. The right models and tools depends on data volume, forecast horizon, interpretability needs, computational budget, and problem characteristics.

The evolution doesn’t mean foundation models replaced everything. This selection of options however represents the field’s strength. The challenge and opportunity at the same time is in developing the best approach where it fits best.

Where We Are in 2025

About ~71% of data scientists are now exploring foundation model-based forecasting techniques, while 58% of enterprises have adopted transformer-based time series models. The most compelling evidence to “Why?” comes from business impact.

Walmart’s produce transformation illustrates the scale of potential savings. When the Eden system launched in 2018 to screen produce using machine learning, it saved $86 million in the first six months. The company has since deployed additional AI systems, including a Self-Healing Inventory platform that generated $55+ million in savings through 2025. Airlines have achieved between $500 million and $1 billion in operational savings through improved pricing and demand forecasting systems. Every empty seat represents lost revenue; every overbooked flight creates customer service problems. Better forecasting enables fuller planes with happy passengers enjoying to travel.

Healthcare systems have had over $150 million in efficiency gains through advanced forecasting for staffing and resource allocation. More importantly, better predictions mean patients receive care when needed and nurses avoid being overworked. The 2022 Winter Olympics deployed Autoformer for weather forecasting and resource planning. Zalando, Europe’s fashion platform, implemented transformer-based models for demand forecasting across their e-commerce operations. In fashion, 10% forecasting errors mean either stockouts of trendy items or warehouses full of unwanted inventory from last season.

Modern foundation models achieve 75-90% accuracy on multivariate problems, a substantial improvement over the 50-60% accuracy from mid-2010s statistical methods. However, performance varies. TimesFM performs particularly well on daily data, TimeGPT works well on monthly aggregates and specialized models like Toto show strong results on domain-specific metrics.

No single model dominates across all scenarios however!

Different approaches show advantages in different contexts:

State space models: Mamba and similar architectures offer linear-time sequence modeling as alternatives to transformers, works better for long contexts.

MLP-based approaches: TSMixer, TTM, and N-BEATS show competitive performance with simpler architectures that train faster and require less memory.

Hybrid methods: Combinations of ARIMA, Prophet, and neural networks often outperform pure deep learning approaches, particularly for smaller datasets or when interpretability matters.

Classical statistical methods: ARIMA, exponential smoothing and Prophet remain effective when data is limited, interpretability is required or someone is compute constrainted.

This space hasn’t converged on foundation models as a universal solution to all problems however the selection of tools and models means choosing the right approach for each problem matters more than ever.

The Future of Forecasting

Eight trends are developing, each addressing different limitations of current approaches:

1. Multimodal Integration

Forecasting systems are combining multiple data types in unified models. Time-LLM (2024) provides natural language explanations alongside predictions. UniTime enables domain adaptation using text instructions rather than full retraining.

Systems integrate satellite imagery, social media, IoT sensor data, economic indicators, news feeds and weather patterns. Early implementations show 15-30% accuracy improvements from combining multiple signal types, enabling forecasting that incorporates broader contextual signals beyond just historical patterns.

2. Causal Reasoning

Moving from correlation-based forecasting to understanding cause-and-effect relationships. Traditional models predict outcomes but don’t explain underlying mechanisms or support intervention analysis. New causal transformer architectures enable counterfactual analysis like “what if we discount by 20% in the Southeast?” with impact estimates.

Early adopters report 40-60% better decision outcomes through scenario analysis. Challenges: distinguishing causation from correlation, requiring domain expertise for validation and higher computate costs than standard forecasting.

3. Enhanced Probabilistic Forecasting

Recent developments improve uncertainty quantification beyond basic quantile estimates:

Conformal prediction: Distribution-free uncertainty quantification with mathematical coverage guarantees.

Calibrated uncertainty: Ensuring predicted probabilities match observed frequencies across confidence levels.

Multi-horizon uncertainty: Understanding how forecast uncertainty evolves over different time horizons.

Companies report 20-40% improvements. Works well for inventory management, capacity planning and risk assessment.

4. Continual and Online Learning

Traditional models require periodic retraining on historical data. Continual learning enables incremental updates as new data arrives. Particularly valuable for financial markets, social media trends and IoT sensor networks where patterns change frequently.

5. Graph Neural Networks for Spatial-Temporal Forecasting

Models interconnected systems where relationships between entities matter. GNNs model spatial dependencies explicitly, traffic flow across road networks, disease spread across regions, inventory across supply chain nodes, sensor readings across manufacturing facilities.

GNN approaches like DCRNN, Graph WaveNet, and MTGNN demonstrate 10-25% accuracy improvements over traditional methods on problems with strong spatial dependencies. Applications include urban traffic prediction, epidemiological forecasting, supply chain optimization, energy grid management and others.

6. Hierarchical Forecasting

Organizations need forecasts at multiple aggregation levels that remain consistent, individual SKUs must aggregate correctly to category and total store forecasts; regional forecasts must sum to national totals. Traditional approaches forecast each level independently.

Approaches like MinT (minimum trace reconciliation) and probabilistic hierarchical forecasting achieve 15-30% better accuracy than independent forecasts. Particularly valuable for retail, supply chain, and financial planning.

7. Efficiency and Edge Deployment

Through distillation, quantization, and edge-optimized architectures, models are becoming significantly more efficient. TimeGPT Mini: 47M params, <15ms. TTM: <1M params, <10ms CPU inference. This represents 100-1,000× cost reductions over three years, enabling forecasting on edge devices and IoT sensors rather than requiring cloud infrastructure.

Currently 8% of deployments, edge forecasting is growing 100% annually, expected to reach 25-30% by 2027.

8. Greater LLM Integration

Large language models enhance time series forecasting systems, focused on usability and interpretability rather than raw accuracy. Emerging capabilities include:

Natural language explanations of predictions and anomalies.

Adjusting forecasts based on text-described scenarios without model retraining.

Generating and evaluating multiple scenarios.

Incorporating domain knowledge from documentation alongside statistical patterns.

Early results show 25-40% improvement in human-AI collaboration effectiveness, with expected 3-5× productivity improvements for data scientists.

The Road Ahead

The evolution of time series forecasting shows a pattern: breakthroughs come from understanding why previous approaches failed.

ARIMA worked until data became too large and complex. Deep learning promised a solution but initially struggled because LSTM architectures weren’t optimized. The M4 Competition taught us that hybrid approaches often outperform pure methods. Transformers needed domain-specific details to work effectively. Foundation models succeeded by combining innovations with scale.

We’ve progressed from 50-60% accuracy (mid-2010s statistical methods) to 75-90% accuracy (modern foundation models) on multivariate problems. We’ve moved from training separate models for every time series to zero-shot across domains. We’ve evolved from point predictions to full probability distributions that quantify uncertainty.

The next chapter won’t be about abandoning models for something entirely new. Instead, we’ll see:

Domain-specific foundation models for healthcare, finance, retail, manufacturing and other areas.

Smaller, faster, cheaper models that run on edge devices and bring forecasting to organizations without big budgets.

Combining the best of worlds - statistical methods with foundation models.

Moving from basic quantile estimates to full distribution modeling with calibrated probabilities

LLM interfaces that make forecasting accessible to everyone and strengthening Human-AI collaboration.

The transformation isn’t that foundation models replaced everything that came before. It’s that we now have additional models for problems that were previously impossible or hard to solve.

As we look toward 2026 and beyond, the field of time series forecasting has never been more exciting. The tools exist. The infrastructure is maturing. Everything is there to start building.

Wishing you an amazing week ahead, one filled with new ideas, possibilities, and success! ✨

If you found this edition valuable, share it with a friend who’s just as curious about AI. 😎

Start building. Start growing. 🌱📈

References

TimesFM (Google, December 2023)

Paper: “A decoder-only foundation model for time-series forecasting”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.10688

GitHub: https://github.com/google-research/timesfm

Chronos (Amazon, March 2024)

Paper: “Chronos: Learning the Language of Time Series”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.07815

GitHub: https://github.com/amazon-science/chronos-forecasting

Chronos-Bolt (Amazon, October 2024)

Paper: “Chronos-Bolt: Efficient Pre-trained Time Series Foundation Models via Knowledge Distillation”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.09366

GitHub: https://github.com/amazon-science/chronos-forecasting

MOIRAI (Salesforce, March 2024)

Paper: “Unified Training of Universal Time Series Forecasting Transformers”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.02592

GitHub: https://github.com/salesforce/moirai

TimeGPT (Nixtla, 2023-2024)

Paper: “TimeGPT-1”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.03589

GitHub: https://github.com/Nixtla/nixtla

API Documentation: https://docs.nixtla.io/

Tiny Time Mixers / TTM (IBM, October 2024)

Paper: “Tiny Time Mixers (TTMs): Fast Pre-trained Models for Enhanced Zero/Few-Shot Forecasting of Multivariate Time Series”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.03955

GitHub: https://github.com/ibm-granite/granite-tsfm

MOMENT (Carnegie Mellon, October 2023)

Paper: “MOMENT: A Family of Open Time-series Foundation Models”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.03885

GitHub: https://github.com/moment-timeseries-foundation-model/moment

Timer (Tsinghua University, 2024)

Paper: “Timer: Transformers for Time Series Analysis at Scale”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.02368

GitHub: https://github.com/thuml/Timer

Lag-Llama (ServiceNow Research, October 2023)

Paper: “Lag-Llama: Towards Foundation Models for Time Series Forecasting”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.08278

GitHub: https://github.com/time-series-foundation-models/lag-llama

Toto (Datadog, 2024)

GitHub: https://github.com/DataDog/toto

Blog Post: https://www.datadoghq.com/blog/datadog-time-series-foundation-model/

Informer (2021)

Paper: “Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting” (AAAI 2021)

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2012.07436

GitHub: https://github.com/zhouhaoyi/Informer2020

Autoformer (2021)

Paper: “Autoformer: Decomposition Transformers with Auto-Correlation for Long-Term Series Forecasting” (NeurIPS 2021)

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.13008

GitHub: https://github.com/thuml/Autoformer

FEDformer (2022)

Paper: “FEDformer: Frequency Enhanced Decomposed Transformer for Long-term Series Forecasting” (ICML 2022)

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.12740

GitHub: https://github.com/MAZiqing/FEDformer

DLinear (2023)

Paper: “Are Transformers Effective for Time Series Forecasting?” (AAAI 2023)

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.13504

GitHub: https://github.com/cure-lab/LTSF-Linear

PatchTST (2023)

Paper: “A Time Series is Worth 64 Words: Long-term Forecasting with Transformers” (ICLR 2023)

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.14730

GitHub: https://github.com/yuqinie98/PatchTST

iTransformer (2024)

Paper: “iTransformer: Inverted Transformers Are Effective for Time Series Forecasting” (ICLR 2024)

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06625

GitHub: https://github.com/thuml/iTransformer

TSMixer (2023)

Paper: “TSMixer: An All-MLP Architecture for Time Series Forecasting”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.06053

GitHub: https://github.com/google-research/google-research/tree/master/tsmixer

AlexNet (2012)

Paper: “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks” (NeurIPS 2012)

Paper Link: https://papers.nips.cc/paper/2012/hash/c399862d3b9d6b76c8436e924a68c45b-Abstract.html

LSTM (1997)

Paper: “Long Short-Term Memory”

Neural Computation, 9(8), 1735-1780

WaveNet (2016)

Paper: “WaveNet: A Generative Model for Raw Audio”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.03499

Blog Post: https://deepmind.google/discover/blog/wavenet-a-generative-model-for-raw-audio/

DeepAR (2017)

Paper: “DeepAR: Probabilistic forecasting with autoregressive recurrent networks”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/1704.04110

N-BEATS (2019)

Paper: “N-BEATS: Neural basis expansion analysis for interpretable time series forecasting” (ICLR 2020)

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.10437

GitHub: https://github.com/ElementAI/N-BEATS

ES-RNN (M4 Competition Winner, 2018)

Paper: “A hybrid method of exponential smoothing and recurrent neural networks for time series forecasting”

International Journal of Forecasting, 36(1), 75-85

ARIMA

Book: “Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control” (5th ed.) by Box, Jenkins, Reinsel, & Ljung. Wiley, 2015.

Exponential Smoothing & Prophet

Free Textbook: “Forecasting: Principles and Practice” (3rd ed.) by Hyndman & Athanasopoulos

Online: https://otexts.com/fpp3/

Prophet (Facebook/Meta, 2017)

Paper: “Forecasting at scale”

The American Statistician, 72(1), 37-45

GitHub: https://github.com/facebook/prophet

Documentation: https://facebook.github.io/prophet/

Time-LLM (2024)

Paper: “Time-LLM: Time Series Forecasting by Reprogramming Large Language Models” (ICLR 2024)

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.01728

GitHub: https://github.com/KimMeen/Time-LLM

UniTime (2024)

Paper: “UniTime: A Language-Empowered Unified Model for Cross-Domain Time Series Forecasting”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.09751

GitHub: https://github.com/liuxu77/UniTime

Mamba (State Space Models, 2023)

Paper: “Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.00752

GitHub: https://github.com/state-spaces/mamba

GIFT-Eval (2024)

Paper: “GIFT-Eval: A Benchmark For General Time Series Forecasting Model Evaluation”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.10393

LOTSA Dataset

Paper: “LOTSA Data: Learning with Massive Collections of Time Series from the Web”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.02592

Survey Papers and Overviews

“Transformers in Time Series: A Survey” (IJCAI 2023)

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2202.07125

“On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models”

arXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258

“Foundation Models for Times Series” (ODSC)

Blog: https://odsc.medium.com/foundation-models-for-times-series-1d08272b09a1

Walmart AI Supply Chain (2024)

Datadog Time Series Foundation Model

https://www.datadoghq.com/blog/datadog-time-series-foundation-model/

Google Cloud TimesFM Documentation

https://cloud.google.com/bigquery/docs/timesfm-model

HuggingFace Time Series Arena

https://huggingface.co/spaces/salesforce/timeseries-arena

Papers with Code - Time Series Forecasting

https://paperswithcode.com/task/time-series-forecasting

Hey, great read as always. This article really builds on your earlier dissucsions about foundation models, showing their impact on time series forecasting. Very insightful.

This is hands down the most comprehensive overview of time series forecasting evolution I've read! The way you connected 50+ years of progress from ARIMA through modern foundation models really shows how each era built on lessons from the previous one. The Datadog Toto callout is particuarly interesting - domain-specialized foundation models (151M params on 2.36 trillion IT telemetry tokens) achieving 15-20% better accuracy than general models shows that vertical optimization still matters even in the foundation model era. Your point about the M4 competition revealing that ES-RNN hybrid outperformed pure deep learning is a great reminder that newer isn't always better. The future trends section is exciting especially multimodal integration and causal reasoning. Great work pulling together all these references!